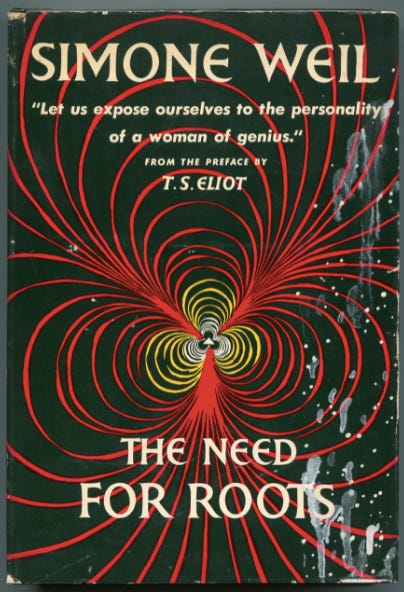

Not long after sending out my very first newsletter, Andy came home one day to tell me about a podcast he had just listened to. It was about the philosopher Simone Weil — contemporary of the other Simone — and her book, The Need for Roots.

“It’ll be right up your alley”, Andy told me. So the next day, after years of seeing her name on the shelves of French bookshops and never picking her up, I went out and bought it.

Simone Weil is known for being a woman of her word. When the Spanish Civil War started, she didn’t just sit around talking about how dreadful it was. She set off for Spain and, despite being a short-sighted pacifist with no skill for shooting, joined the fight. When she got home and her middle-class mates were railing against factory conditions, she didn’t just nod along and agree with them. She got herself a job in a factory to better understand and defend the working class. And when the Second World War broke out, you’d better believe she made herself a pillar of the Free French government (albeit from London, in exile).

Right before her death, at age 34 from complications with tuberculosis (again, living by her word, she refused to eat anything more than what she believed people in German-occupied France were eating), The Need for Roots was commissioned as a plan for renewal and recovery post-Nazi occupation. And while the conditions of WWII may seem far from where we are today, it’s important to remember that the people then were human just as we are human now, and experienced the same needs for belonging and rootedness as we do.

So, I thought I would use this newsletter to lay down some wisdom (Simone’s) and share some thoughts (my own) from a few passages that rang so true and felt so relevant, as a little ode to the Patron Saint of All Outsiders.

To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognised need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain expectations for the future. This participation is a natural one, in the sense that it is automatically brought about by place, conditions of birth, profession and social surroundings. Every human being needs to have multiple roots. It is necessary for him to draw wellnigh (almost) the whole of his moral, intellectual and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he forms a natural part.

When I read this passage from the opening of Part II of the book, I literally gasped at how perfectly it gets to the root (pun, oops) of why I started this newsletter in the first place. Not only in how it highlights the importance of involvement with one’s community and a connection to a particular place, but also the need to nurture the more abstract facets of one’s life. Simone herself is the ideal example of this, rooting herself in her values, working hard to understand what she believed in, and standing by those beliefs.

This passage also conjures, to me, the image of a web. A reminder that life isn’t lived on a single thread of work or love or getting a six-pack. It’s a tapestry. A network of roots that knots together to form a rich whole that every part of needs tending to. Because, as Simone says, “a tree whose roots are almost entirely eaten away falls at the first blow.”

Money destroys human roots wherever they are able to penetrate, by turning desire for gain into the sole motive. It easily manages to outweigh all other motives, because the effort it demands of the mind is so very much less. Nothing is so clear and so simple as a row of figures.

When I was in Tasmania earlier this year, I visited an exhibit at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery all about the Tasmanian Aboriginal people who had lived on the island for millennia before colonialists arrived and pretty much wiped them out. It talked about their ways of life, their languages and tools, and their deep connection to every plant, animal, stone, element, and landscape that surrounded them. A connection so profound and that fostered such a strong sense of belonging and rootedness that when they were removed from these lands, they often fell ill and even died.

When I left the exhibit, I thought for a long time about what people are connected to now. Family, maybe? Our home towns? Also maybe, but not enough to resist moving to the big city. After a while, I realised that what we are probably all most concerned with, whether we know it or not, is Money. And who can blame us? Money makes the world go round. Time is money. You’ve gotta pay the bills. And with this being the case, it’s easy to lose sight of the other, more complex, more abstract, and often, more important things.

Following this line of thought took me back to an idea I came across in Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind by Yuval Noah Harari. He writes that “money, in fact, is the most successful story ever invented and told by humans, because it is the only story that everyone believes.” Money is a fiction, and yet we live our lives by it even more than we live it by family, friendship, nature, art, or intellect.

There is no denying the importance of money, but I took these few lines from Simone as a reminder not to be taken for a ride by it. Not to let the other elements of my life go untended in favour or in fear of the tides of cash flow.

A lot of people think that a little peasant boy of the present day who goes to primary school knows more than Pythagoras did, simply because he can repeat parrot-wise that the earth moves around the sun. In actual fact, he no longer looks up at the heavens. The sun about which they talk to him in class hasn’t, for him, the slightest connection with the one he can see. He is severed from the universe surrounding him.

I have a couple of thoughts about this final quote. Firstly, the feeling that we all know everything these days without really knowing anything at all — a paradox that reminds me of the adage, “Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit. Wisdom is knowing not to use it in a fruit salad.” And there are a lot of tomatoes getting around in fruit salads these days, if you know what I mean.

Secondly, and more relevant to the topic of roots, is this kind of dissociation from the world around us. But instead of falling head-first into a rant about humanity failing to pay attention, I am going to turn this into a whimsical exercise in re-association with the help of the changing seasons.

In the Northern Hemisphere, we have recently entered Spring. We all know it because the clocks sprung forward, the blossoms have bloomed, and the temperatures are slowly but surely rising.

But it’s kind of nice to dig a little deeper than the thrill of wearing a lighter jacket and consider what the changing seasons mean for us personally.

I tried writing down some examples, but it just turned into something out of Cinderella, so I will leave this as a little prompt to look back up to the heavens, so to speak, and rekindle some connection to the world around us that Simone believed us to have lost.

See you in the next one,

Annabel

Just a quick note to say that last week I reached 100 subscribers — Thank you so much!

If you are enjoying the newsletter, I’d love it if you could share it with a friend who you think might like it too.

And if you’ve got any feedback or suggestions, just reply to this email. I’d love to hear from you!